The Impact of Systemic Racism in America on Competitive English Riding

In the summer of 2020, the murder of George Floyd triggered protests, social justice movements, and nationwide discussion about how systemic racism affects every aspect of American life. The equine industry was not exempt from the conversation.

On June 1, 2020, The Chronicle of the Horse published an opinion piece penned by elite junior rider Sophie Gochman, entitled “Breaking The Silence Surrounding White Privilege In The Horse World.” In that article, Gochman called for those with power in the equestrian community to utilize that power to enact change and dismantle racism and social inequality. She communicated her frustration that others in the community were publicly silent on this issue, and asserted that silence was no longer acceptable.

Gochman’s piece sparked a flurry of discussion and controversy, including a response piece from elite trainer and horsewoman Missy Clark that was published just one week later entitled “Sometimes You Have to Read Between the Lines.” Clark’s piece was essentially a defense of the equestrian community, asserting that there is little to no racism in the equestrian community, that any exclusions of minority groups are not purposeful (and therefore not discrimination), and that Gochman’s perceptions of the equestrian community were inaccurate and inflammatory. While Clark recognized the existence of white privilege in her piece, she also insisted that discrimination did not exist in the equestrian community because the people that she knew and had experience with used their privilege to give to others.

These two articles represented two factions of people within the equestrian community. The first group, represented in Gochman’s article, are those who see and are upset by the inequalities in our sport. They want change, and prioritize diversity and accessibility efforts that acknowledge and make accommodations for social inequities. The second group, represented by Clark, are of the belief that there is no racism or discrimination within the community and that, through hard work and a little bit of luck, anyone can reach their goals. For example, in Clark’s piece, she wrote,

“Because you may not see a majority of certain presences doesn’t mean there have been purposeful exclusions. In our world, some choices are forced because they’re based on the cold hard fact most people can’t afford to do this. It doesn’t mean that it’s fair, but it also doesn’t mean that it’s discrimination.”

It becomes relevant here to understand the difference between discriminatory behavior and systemic discrimination, or more specifically, individual racism and systemic racism. The Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre defines individual racism as,

“…an individual’s racist assumptions, beliefs or behaviors…”

and systemic racism as

“…the policies and practices entrenched in established institutions, which result in the exclusion or promotion of designated groups.”

Clark may be correct that most equestrians do not actively engage in racist or discriminatory behavior, at least not on a conscious level. However, even if Clark is correct, this lack of individual racism does not necessarily negate the existence of systemic racism, and unfortunately, at this point in the conversation, we have a constant stream of information and black voices telling us that there is individual discrimination and racism in our sport.

Equestrians of color have reported feeling unwelcome and unwanted – no matter how welcoming the predominantly white equestrian community feels that they are being. 17 year-old Lauryn Gray put it extremely well in her 2020 article “Being a Bay in a Sea of Grays” when she said,

“My barn and the circuit I compete on have always been an extremely loving and accepting environment, but now that I’m no longer looking through rose-colored glasses, I realize that the same can’t be said about our community as a whole.”

This community Gray and Clark both refer to is built on the same racist structures as the rest of our country and “getting in” to obtain that wonderful feeling of community support is harder for people who are not white. Clark’s mention of “financial constraints” in her piece alludes to this but seems to imply that financial constraints are not tied to race, when in fact they are.

Additionally, while it is true that many people of financial privilege make donations to help those who are less privileged and that many people treat others with respect, individual acts of charity or kindness alone cannot solve systemic-level problems or compensate for the microaggressions and discriminatory behavior of others. I would hope that those who are in power due to their privilege now will recognize that they benefit from racist structures that were formed long ago but are currently perpetuated by the silence of the elite.

Clark’s piece also failed to acknowledge the connection between whiteness and wealth. People of color have been legally and socially shut out of the same opportunities as white people in America, and this exclusion has disallowed them from building generational wealth and accumulating the sort of net worth required to compete in equestrian sports.

I laid out costs at each of the four levels of riding in the second entry to this series and, in the first entry, shared that, according to the United States Equestrian Federation 2022 Media Kit, the average net worth of a USEF member (which indicates eligibility to compete in recognized competition) was $955,000 with an average yearly income of $185,000 while data from The U.S. Census Bureau indicated that the average American household headed by a white person earned about $70,000 per year with an average net worth of $162,770, while the average American household headed by a black person earned about $41,000 per year with an average net worth of $16,300. While the average household in both racial groups falls far below the average wealth of a USEF member – however, the census data clearly lays out how much more “above average” a black household has to be.

Level 1

Although level one (access to horses/riding) is the most accessible, barriers such as cost, location, and family/community support may still inhibit participation. I’ve already discussed how the cost barrier disproportionately affects people of color, and the other two items on my list aren’t exceptions to the rule.

Because of the land requirements for horse farms, most are based in suburban or rural areas, with very few riding opportunities available in cities or urban areas. Discriminatory practices in real estate such as redlining and gentrification created segregation in housing, often forcing people of color into urban housing projects with decreased access to horses/riding.

Additionally, even as the effects of these practices begin to slowly decline, the equestrian community remains infamously insular – many riders only start because they have a friend or family member who already rides and can connect them with a quality instructor/lesson program. Due to lack of ability to build generational wealth and have convenient geographic access, people of color are less likely to have these connections that can get them started than their white counterparts.

Level 2

As Clark mentioned in her piece, accepting environments do exist for people of color in the equestrian community, however, getting involved in competitions exposes individuals to groups outside of their own environment. Equestrians of Color is a group blog that shares photo essays telling the stories of people of color who ride. Nearly every featured person mentions facing microaggressions and discriminatory comments and/or feeling underrepresented in the sport.

Levels 3 and 4

This brings me to my discussion of the last two levels: rated – elite competitions. Our sport is overwhelmingly white at the top levels. 89% of USEF members are white, and no person of color has ever represented the United States at the Olympics. The USEF is not blind to this issue. Their diversity statement reads,

“Diversity and inclusion are fundamental to US Equestrian’s vision: To bring the joy of horse sports to as many people as possible. We recognize the need to achieve increased diversity and that our growth and success depends on the inclusion of all people. We are committed to providing access and opportunity for people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, veterans and active military personnel, people with disabilities, and those of all ages, religions, ancestries, genders and gender identities, and economic status to harness the synergy of diverse talents.”

Despite this statement, I believe that USEF, other governing bodies, and representatives of the sport can and must take a more active role in recognizing the scope of the issue in order to effectively address it.

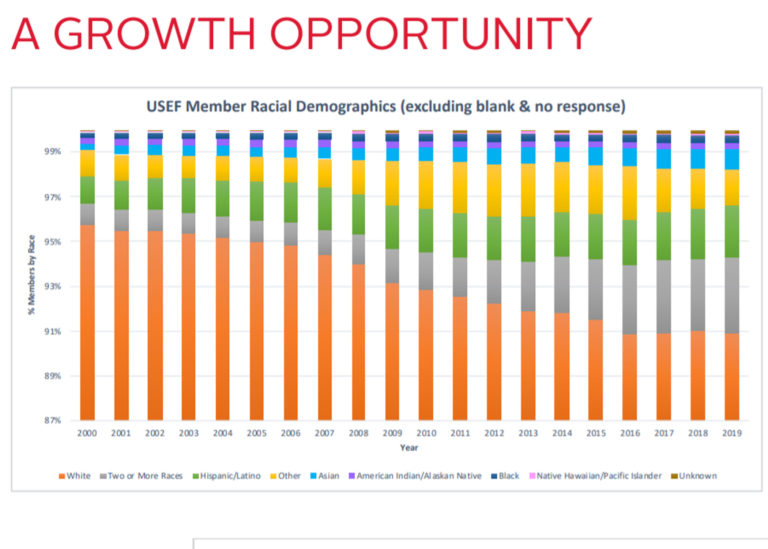

For example, the figure to the left is included in the USEF Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Action Plan. While I believe that the plan itself was well-created, relying on input from people of diverse backgrounds and experiences, this figure specifically is misleading and, in my mind, representative of a desire to minimize the issue and emphasize progress.

At first glance, the graph makes it appear that, as of 2019, the equestrian community is extremely diverse, with mixed race individuals represented almost as often as white individuals. However, if you look closely at the vertical axis, you’ll notice that the bottom of the graph cuts off at 87%, not 0, which skews the visual data.

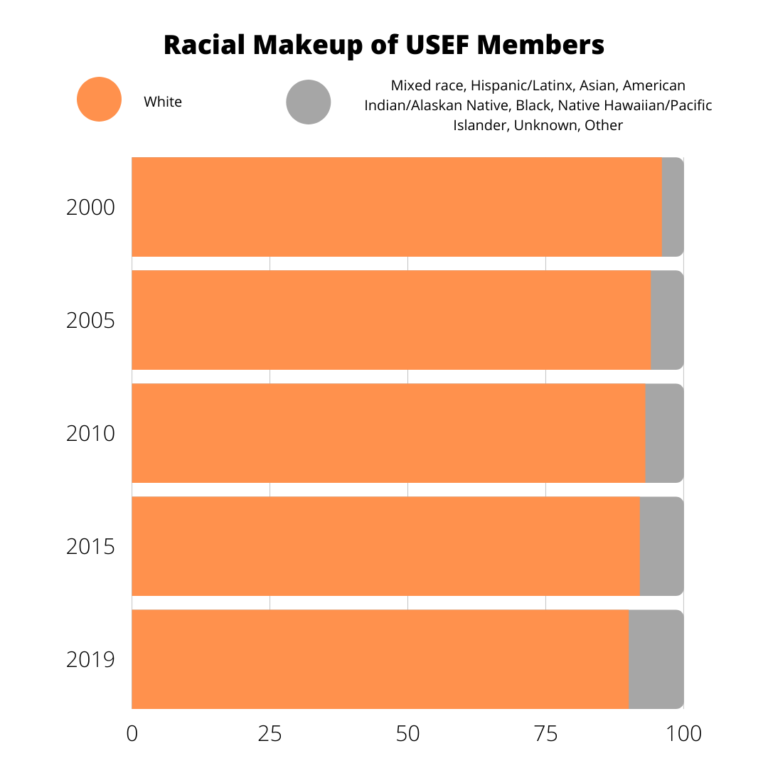

A more accurate representation of USEF racial demographics in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2019 is depicted below on the left. While the trend of increasing diversity still holds, this second graph shows just how overwhelmingly white our sport is.

Additionally, the United States Census Bureau 2020 results on race show that (unless there was a drastic change in USEF membership between 2019 and 2020), white individuals are overrepresented by about 30% in the USEF.

Overall, while USEF is taking important steps towards increasing diversity, equity and inclusion in our sport, those steps will only be useful if we as a community take full accountability of the scope of the problem, which includes using accurate graphics and reporting as well as coming to terms with the uncomfortable truth that even people we know, love, and trust (or even ourselves) may be perpetuating racism in our sport.

Once we’ve acknowledged the problem, the next step is addressing it. In Clark’s piece, she defended the community by saying,

“Many Olympians and trainers are proactive in ways that aren’t directly in the forefront. Change in thought and action can be achieved in both big and small ways, in loud and in quiet ways. Any vehicle towards change is a valid one. Some people seek change peacefully; some preach from the rooftops. The Olympians and trainers who I know are absolutely outraged by the complete disregard for George Floyd’s life by the four police officers from Minneapolis. It’s clear there’s a vast divide, and our country is in a state of turmoil like never before.”

This statement is true, and important. There are many ways to be an activist and to dismantle systems that are outdated and no longer reflect the beliefs and attitudes of our community. However, if every person chooses to attempt to achieve change via the small, quiet methods, then that change is going to take a lot longer than if people in power use their platforms to take the louder, bigger options. I hope that these Olympians and trainers who Clark refers to take that outrage and use their power to turn it into something productive that will better the community as a whole.

Clark also called on Gochman (and other equestrians) to “figure out different ways to achieve a goal” and cites the protesting methods of Martin Luther King Jr., Desmond Tutu, Mother Teresa, John Lennon, Mahatma Gandhi, and Harriet Tubman specifically. She states that these people “…advocated for equality, world peace, compassion and humanity [and] made lasting impressions in history because they tried to influence in peaceful ways.”

However, each of these people cited by Clark made change in loud, disruptive ways that caused immense upset among the dominant social groups. Martin Luther King Jr. made a speech in 1968 called “The Other America” in which he asserted that although he still believed in the power of nonviolence, he could not condemn riots.. Desmond Tutu was arrested during a protest in 1989. Mother Teresa lobbied to leave her convent so that she could aid the poor of Calcutta and continuously used her voice to aid others. John Lennon invited the media into his hotel room. Mahatma Gandhi was arrested multiple times and said that, “…non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as is cooperation with good.” Harriet Tubman was the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the Civil War.

Peaceful protest for these people did not consist of silence or “behind the scenes” activism. Peaceful did not mean quiet and it did not mean complacent.

We all have to recognize how the issue of systemic racism affects the equestrian world. To do this, it is important to seek out and amplify diverse perspectives. As part of this, I hope that equine publications will continue to share pieces from people of color as part of their regularly scheduled content. I also hope that those in power in the equestrian world – those people who represent us and speak for us and carry a huge amount of wealth – use their platforms to make real change.

Something wonderful about the horse world is that we are always helping each other – filling a class so someone can qualify for their finals, wiping off a stranger’s boots, or helping with barn chores. Now, our sport itself needs help and young riders are demanding change. Let’s not disappoint them.