Suck it In or Suck it Up: How Different Body Types are Treated in English Riding

Weight and body type is an infamously divisive subject, and the equestrian world is in no way exempt from the discussion. From the first lesson to competing in the international ring, no body is safe from scrutiny. Aspiring equestrians with larger bodies may be turned away from lessons or opportunities right from the beginning. In disciplines that are judged more subjectively, body types that do not appear to be long, tall, and thin may be penalized, given lower scores, or given fewer opportunities in the show ring – an effect that can make it more difficult to build experience, improve as a rider, and potentially even start a riding career. In this entry in my series examining accessibility in English riding, I’ll explore how body image, body-shaming, and body types affect riding at each of the four levels: consistent lessons/access to horses, local shows, state/rated shows, and national/international level competition.

Level One: Access to Horses

As discussed in the first entry in this series, riders who have larger bodies, especially women, may face discrimination under the guise of animal welfare. Some barns will implement weight maximums to join their lesson programs, and they do not always match the recommended weight limits or veterinary recommendations.

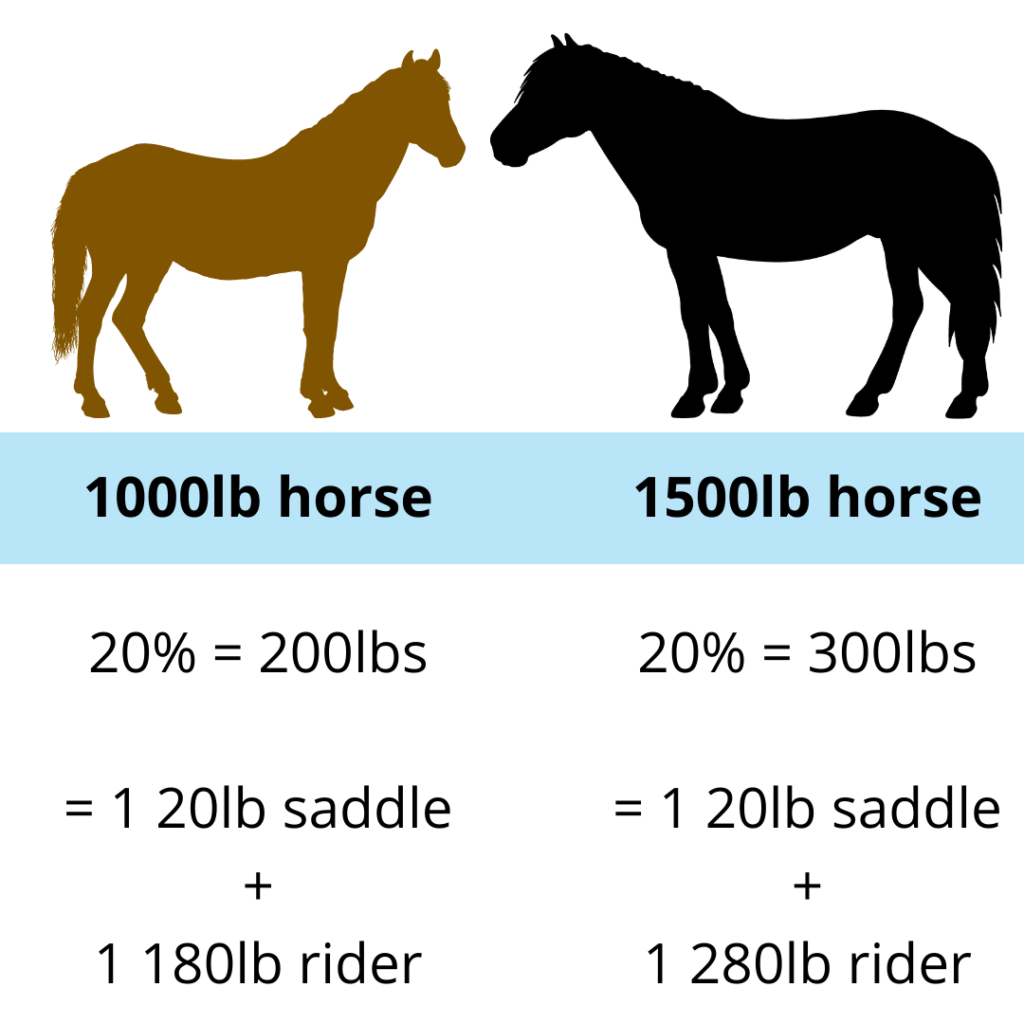

Each horse’s needs and limitations should be determined by a vet and qualified care team, however, a commonly recommended weight limit for horses is approximately 20% of their body weight, which indicates that the average smaller-breed horse (weighing around 1,000lbs) should be able to carry riders weighing up to 180lbs and larger breeds (weighing around 1,500lbs) should be able to carry riders weighing up to around 280lbs. Draft horses can weigh upwards of 2,000lbs, increasing their carrying capacity even more.

In a qualitative study conducted with students who participated in collegiate riding programs, one rider (who was described as shorter and heavier than the other study participants) mentioned that riding made her feel as though she needed to lose weight and that she was too short.

She stated that some people were just built to be riders, and others just weren’t. Her coach was also abusive, encouraging competition between teammates, operating with the slogan “Thin Wins,” and telling the rider that while she couldn’t change her build, she could make it thinner.

At the time of the study, this rider in particular had quit the riding team, which goes to show the effect that discriminatory and abusive behavior/practices can have on the aspiring equestrian.

An illustration of the commonly used "20% rule"

Level Two: Local Shows

Once competitions come into the picture, the discrimination becomes more overt. In the same study mentioned above, the word “thin” was mentioned 777 times and every rider (including those in Western disciplines) acknowledged that there was a competitive advantage to having a tall and thin body type. One rider who self-described as having that body type reported that competing in horse shows had increased her confidence, although she also acknowledged that she may not have deserved all of the top placings she had been awarded.

As a junior rider, I competed in the hunters and equitation and had a similar experience as the first rider from the study. When I first started showing, like many other young riders, I dreamt of doing the big equitation medal classes, but quickly discovered that it wouldn’t be attainable. While I consistently placed well and had strong rides, especially in my last years competing, I won first place only a handful of times, and each time required a near-perfect performance. Other girls on my team who were taller or thinner but were similar in skill (or even less experienced than I was) received much better results. Time and time again, I witnessed riders who were tall and thin make mistakes and still win – mistakes that I, as a shorter and heavier rider, could not have afforded to make.

Especially as I got older, I understood the system and was able to conceptualize that my performance would not always match the points that I was awarded. I also knew intellectually that my body was healthy and strong. However, constantly losing out to taller/thinner riders still deeply affected my self-esteem and motivation to progress in the sport.

The picture on the left is of me (mounted) with my teammates when I was around 16 years old. Our team varied in age from around 12 years old to 18 years old. When we took team pictures, I remember looking at them for weeks afterward. I felt that I looked disgustingly large next to my teammates and couldn’t stop comparing my body – which was still growing and changing – to those around me, even the younger riders who were at a completely different stage of life.

This comparison was further perpetuated by the constant cues I had around me. At 16, I was buying the largest possible size of tall boots and half chaps – cementing in my mind that nobody could possibly be larger than me and that my (incredibly normal) body was a gross outlier. I heard riders I admired talk about how they needed to lose weight to win and I heard their trainers encourage the behavior.

In college, I tried out for the equitation team three times and didn’t make it. At one point, as part of a conversation about this subject, a coach admitted to me that between me and another rider who was at the same skill level but had long legs and a thin frame, they would pick the other rider to compete every time – not because they believed I wasn’t as qualified but because they knew that we would be judged differently by the judges in our area.

Over the years, it became incredibly clear to me that while it wouldn’t be impossible for me to be competitive in the equitation, I would have to ride that much better to make up for every lost inch and gained pound – and some days it still wouldn’t be enough. Somewhere along the way, I stopped wanting to try – and I was one of the lucky ones. Many riders that do continue on to the highest levels, especially juniors, end up harming their bodies through disordered eating habits that become almost standard for the equitation divisions.

My experience isn’t unique. Even now that I have stepped back from competition, I’ve observed my taller and thinner friends win more frequently in the show ring and receive more opportunities outside of it. While my friends are all extremely hard-working and talented riders, I cannot ignore the possibility that sometimes their blue ribbons or extra rides come at the expense of a shorter or heavier rider who is just as hard-working and talented.

If we want to continue to develop diverse talent in our sport and encourage hard work in riders of all shapes and sizes, we have to do better than that.

Levels Three and Four: Rated Competition through the National/International Level

This brings me to my discussion of rated competitions. National governing bodies like USEF that host or certify these events generally set the standard for judging, which trickles down into local shows and influences state/local associations as well. At these shows, the judges rule all. Coaches make plans for their riders and horses based on what the judges will think and riders bend over backwards to make the judge give them a second look. The bottom line is that what the judge says, goes, and riders and coaches alike spend a great deal of time training based on what they think the judge will say.

The unfortunate reality is that most riders and coaches reasonably believe that judges will award a tall and thin body and penalize a short or heavy one. It makes sense that they would believe that, and it may not even be the judge’s fault. According to the National Eating Disorders Association, weight stigma is firmly ingrained in our culture, even to the point of affecting medical care. If weight stigma can affect an issue as serious as healthcare, what is to keep it from affecting a horse show?

The unfortunate truth is that any competition that depends on human judgement will be affected by bias, including weight stigma. However, there are a few ways to address the influence of bias in judging on our sport.

First, implementing more objective judging systems into disciplines that currently operate under more subjective rules could help mitigate some of the effect of biases on competition results. While the USEF rulebook has specifications for how the rider’s body should be positioned in equitation classes, it also states that riders should “have a workmanlike appearance” – a phrase that leaves room for judges to justify choices that may be influenced by bias.

Additionally, riders traditionally do not receive the judge’s scorecards or comments after a class in the equitation or hunter/jumper classes. This differs from other disciplines, like dressage, where judges score each movement out of ten and then give scores for the overall quality of the gaits, impulsion (energy), submission, rider position (so defined as being in balance with the horse), rider effectiveness of the aids, and accuracy in completing the assigned movements. After their test, the dressage rider will be given their score sheet, complete with the judge’s comments, so that they can understand their score and placement and improve for the next time. While dressage judging certainly isn’t perfect, the format encourages judges to be as fair and objective as possible while also holding them accountable for their decisions and a similar system could be implemented in the hunter/equitation disciplines to similar effect.

Second, there must be a culture shift and it must be addressed from the top level. While each discipline has slightly different rules and processes, judges in America must achieve their “R” certification in order to work at rated shows. Additionally, USEF currently requires all members over the age of 18 to complete a training in “SafeSport” – a program designed to prevent sexual abuse in sports and protect minors.

Adding bias/diversity training requirements into both the R certification process and SafeSport training and having big names in the sport promote the change would go a long way towards demonstrating that fairness and accessibility are priorities in our community. The trainings could also include basic resources and education on disordered eating, weight stigma, and health and fitness to ensure that professionals in our sport are educated on those subjects and prepared to work with people of all shapes, sizes, and backgrounds.

Finally, major equestrian organizations (including governing bodies, retailers, horse show venues, etc.) should include diverse body types and promote fitness over appearance in their marketing, promotion, and public relations. At the time of writing, the USEF-published Equestrian Magazine has not had a plus-size rider represented on the cover anytime in recent history, and other publications have similar trends. While major retailer Dover Saddlery carries plus-size options, every single model in their 132 page catalog appears to be tall and thin. The Smartpak (another leading retailer) website does not perform much better.

This representation is vital to a culture shift in our sport. According to Madison Rose, contributing author to the Medium,

“With bad representation, we can be wired to not love ourselves as much as we should. Or for those outside of our community, they could be wired to not love us as much as they should.”

Overall, through representation, education, and improved systems of judging, we can make the competitive English riding world a more accessible place.