NCEA vs IHSA: Elitism in College Riding

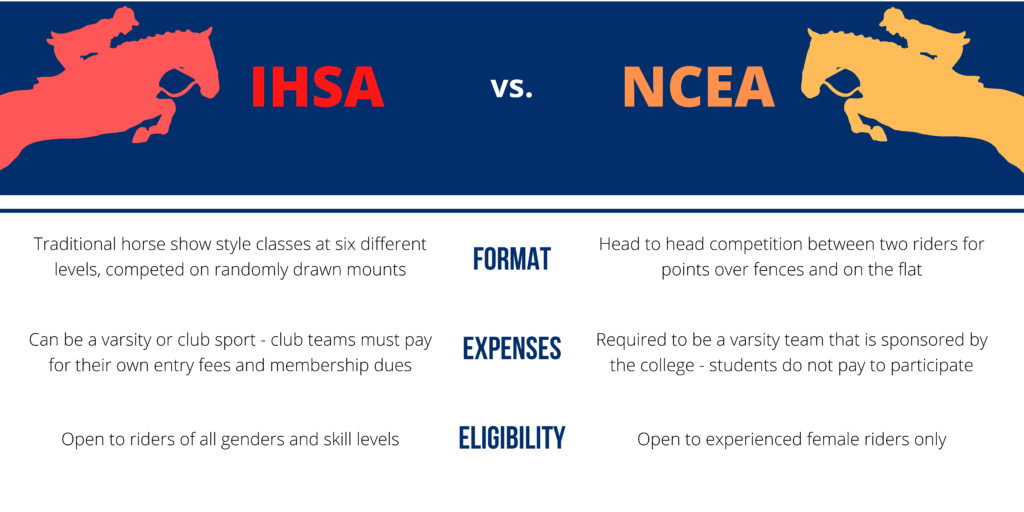

In the first four entries to this series, I discussed barriers to entry such as racism, weight stigma, and costs at four different levels of competitive English riding: access to horses, local competition, rated competition, and national/international level competition. However, there is one subsect of competitive English riding that is not necessarily encompassed in those levels. Collegiate riding comes with its own unique formats, governing bodies, and challenges. Because of these differences, I felt that it was necessary to discuss the issues I’ve mentioned in other entries within the context of college riding by itself. To illustrate my points, I’ll be comparing the two most popular college riding formats and governing bodies: NCEA and IHSA.

The Intercollegiate Horse Show Association (IHSA) was established in 1967 with a mission to “provide equestrian competition for all college and university students regardless of riding level, gender, race, sexual orientation or financial status” with a dedication to “promoting sportsmanship, horsemanship and academic excellence.”

They accomplish this mission by hosting intercollegiate shows in a format that eliminates the requirement of horse ownership, equipment purchases, and prior riding experience. At shows, riders select a mount at random from a pool of horses supplied by the host colleges and compete in divisions ranging from Introductory (where riders are required perform basic tests of position at the walk and trot) to Open (where riders are asked to jump a course of fences set at approximately 3 feet and complete advanced testing at the walk, trot, and canter).

Alternatively, the National Collegiate Equestrian Association (NCEA) is a part of the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA). It was established as an “emerging sport” by the NCAA in 1998 and was formed under the mission of “providing collegiate opportunities for female equestrian student-athletes to compete at the highest level, while embracing equity, diversity and promoting academic and competitive excellence” with a vision of being “recognized globally as the premier level of competition for elite female collegiate equestrian student-athletes.”

The NCEA format is similar to IHSA in that riders compete on randomly drawn horses supplied by the host college, but that is where the similarity stops. Rather than competing within different divisions based on skill, horses from the host college are selected to compete over fences and on the flat. Riders draw their horses, and riders from different teams who draw the same horse compete head-to-head. The rider that receives a higher score on their round earns a point for their team.

The key differences between IHSA and NCEA are that IHSA is designed to allow riders of any background to have the opportunity to compete in college, while NCEA is only an option for riders who are already highly experienced riders, and that NCEA has more objective judging standards than IHSA. I would posit that NCEA competition is thus ultimately more fair than IHSA, but less accessible.

NCEA riders are expected to compete over fences on strange horses at 3 feet or higher, requiring a level of skill that can only be obtained through extensive experience with horses and riding – and that’s just to get on the team.

Riders who are currently competing in NCEA shows include Ava Stearns, the winner of the 2019 Maclay Finals – the most prestigious equitation final for juniors in the United States, Emma Kurtz, who placed top ten in all of the “big three” eq finals – WIHS, THIS, and Maclay Finals in her last year as a junior, and Catalina Peralta – who has trained with and ridden horses owned by Olympians Beezie Madden and McLain Ward and earned reserve champion at the 2021 Maclay Finals (which took place during her freshman year of college). While not every NCEA rider trains with Olympians over the summer, to be competitive against these top-level riders requires a huge amount of experience, which in turn requires an astonishing amount of resources.

As discussed in previous entries, it takes immense financial support to gain experience at the level that is required for NCEA competition. Although the judging standards of competition may be more objective in NCEA than in IHSA, getting a foot in the door to be able to compete requires wealth and privilege that is only available to a small percentage of people. As I outlined in the first entry of this series, monthly costs to ride at this level can easily reach upwards of $2,000. Although NCEA doesn’t directly cost most competitors anything to compete since it is considered a varsity sport by colleges, the amount of experience required to join generally means that it is regardless only available to the wealthy.

Additionally, NCEA is also only available to female riders, which is far from the norm in equestrian competition. Equestrian sports are one of only a handful that allow men and women to compete against each other all the way up to the highest level. In fact, NCEA is the only major governing body of equestrian sports to disallow men from competing entirely, and it is not clear why. The decision to limit eligibility to women, for no clear reason, has the potential to exclude transgender and nonbinary people as well as cisgender men and overall decreases the accessibility of college riding even further.

Alternatively, IHSA is available to riders of all genders and skill levels. While some costs may be associated with competing, especially if the team is not classified as a varsity team at the college it is based out of, they are still significantly lower than the costs associated with standard horse shows. For example, many IHSA members will have to pay for their own training expenses (approx. $200-$300 per month), clothing (detailed here) and membership fees ($45 per year). Club teams often have their members pay dues to cover expenses such as team registration fees and entry fees for competitions (varies per region, but usually $200-$400 per show with 8-12 shows per season). These costs may still be prohibitive to some riders, but are reduced from the expenses associated with horse shows outside of the collegiate format.

Additionally, both IHSA and NCEA have numerous scholarship opportunities available to members and IHSA members also receive discounts on numerous products, including Samshield helmets and gloves, Helite safety vests, and RJ Classics show clothes.

While IHSA is clearly more accessible to join than NCEA, judging standards could be improved. IHSA follows judging standards that are much more traditional than the NCEA format. While NCEA riders compete head-to-head for points, IHSA shows typically have nine classes – Introductory, Pre-Novice (which is not always held at every show), Novice, Limit Flat, Limit Fences, Intermediate Flat, Intermediate Fences, Open Flat, and Open Fences – where the first place rider earns 7 points, second place earns 5 points, third place earns 4 points, fourth place earns 3 points, and so on.

Depending on the show, teams may enter more than one rider in each class. Each rider will earn points towards their individual record, but only one rider (the “point rider”) will have their points count towards the team score. At the end of competition, the lowest-scoring rider has their points dropped from the team score and team awards are given based on which team has the highest amount of points. At the end of the regular season, riders and teams with enough points can progress to regional, zone, and national finals.

The IHSA rulebook contains much of the same wording as the USEF rulebook. For example, the phrase “workmanlike appearance” is used as a judging standard, which, as I have previously discussed, can leave room for judges to allow their own bias to affect judging. This is known to be especially prevalent in the lower level divisions of IHSA. Since riders cannot be tested beyond a few basic tests of position at different gaits, the Introductory, Pre-Novice, and Novice divisions can quickly turn into beauty contests where riders who do not have a tall, thin body type will lose out every time to those who do.

The IHSA rules also leave room for host schools to deny entry to any rider that they decide is too large to ride their horses, which, while designed to protect animal welfare, also leaves room for discrimination without consequence. These things combined mean that IHSA riders often feel encouraged to try to attain a thinner body, sometimes to an unhealthy degree, and sometimes in replacement of developing their skill as a rider. Coaches may also be motivated to further incentivize or even encourage this behavior in order to help their team score the win.

Finally, at least some of IHSA placings are determined by the “luck of the draw,” meaning that your results depend partially on the horse that you draw. While riders can request a re-ride if their horse is determined to be misbehaving to the point that the rider cannot reasonably be expected to manage it and complete their round, re-rides are not always granted and even if a horse is not misbehaving, it may still be more difficult to ride than others in the class. There is always the chance that a rider will be mounted on a horse that is difficult to handle, does not perform the given tests as well as other horses, or simply does not get along well with the rider.

Alternatively, NCEA judging follows more objective standards and has riders compete on the same horse to avoid the “luck of the draw” dilemma in IHSA. While the head-to-head format and judging standards (position of the rider) still leave room for judging bias, NCEA judges are required to announce their numeric scores for each round over fences and on the flat, which promotes accountability and encourages the judge to justify their score. Additionally, flat tests are judged like a dressage test, with each movement receiving a score out of 10 and two additional scores out of 10 awarded for the rider’s position and effectiveness of the aids, which (while again, still imperfect) is significantly more objective than IHSA judging.

Overall, each format has its advantages and areas for growth. NCEA could improve its overall accessibility while IHSA could improve its judging standards, especially at the lower levels. In my opinion, the NCEA should consider either opening competition to men or creating a second division for men while also continuing to reevaluate their policies on transgender athlete inclusion. Additionally, the NCEA claims to be interested in embracing equity and diversity, however, it is exceptionally difficult for anyone outside of the wealthy upper-class to gain the sort of experience required for NCEA competition. One way to resolve this discrepancy would be for the NCEA to develop youth sponsorship programs that would allow young riders to participate in upper-level competition and gain experience, perhaps in partnership with the IEA (Interscholastic Equestrian Association – essentially IHSA for young riders).

In turn, IHSA could adopt some of the judging standards and formats utilized in NCEA to produce fairer competitions. Even small changes such as incorporating more testing into the lower levels and having judges post their scores and comments along with the results would help to hold judges accountable to ethical judging, reduce the effect of biases on results, and encourage riders to focus on developing their skill rather than changing their bodies. In the long-term, depending on the effectiveness of these solutions, the IHSA may consider implementing head-to-head competition or individual flat tests rather than a group flat class as well.

After all, each organization has a responsibility to honor their commitments to provide fair and equitable opportunities to every rider.