When Hard Work Isn’t Enough: The Top Barriers Faced by Aspiring Equestrians

When you think “equestrian,” it’s very likely that a specific image comes to mind. You may be picturing the girl in your third grade class who always wanted to play horses at recess, or a rider in a cowboy hat herding cattle, but it is most likely that you are picturing a tall, thin, rich, white woman who is immaculately dressed in expensive riding clothes and holding the reins of a six-figure horse.

In reality, while the equestrian world has the potential to go far beyond this stereotype and incorporate people of all backgrounds and appearances, it cannot be denied that the stereotypes surrounding it now are rooted in truth – a truth that cannot go unexamined if true inclusion is to be reached.

This series will examine how the issues of wealth discrepancies, racism, and body-shaming form barriers to entry to different levels of involvement in competitive English riding in America. Many equestrians (especially those who compete at the top levels) will tell you that if you put enough hours in, do enough free labor, or ask for enough favors, then you’ll be able to find opportunities that can take you straight to the top. Others have found that this isn’t necessarily true.

I was 14 in the picture at the beginning of this post. I was just starting my competitive riding career on my first lease pony, homeschooling to spend more time at the barn, and working off rides with barn chores. I dreamed of doing the Big Eq – large classes reserved for the best junior riders in the country.

As I got older and more experienced, I would go on to teach lessons, trained horses, and continued to do barn chores in exchange for opportunities and discounted leases/board. I also adjusted my goals to be more realistic – I wanted to compete in the local 3’ equitation (judged on rider position) and jumper (judged on speed) classes and do well in my local equitation leagues to set myself up for a collegiate riding career. However, it was clear to me from an early age that even my modified goals would be a fight to achieve. My life was the barn. I would have done anything for my goals, and it simply wasn’t enough.

When I was in my early teens and still dreaming of competing at the highest levels, my friends and I developed the idea of the “Riding Triangle” to help us conceptualize the difficulties we were facing in reaching our competitive goals. In short, the triangle was made up of three points – wealth, talent, and work ethic. We speculated that anyone could be a good rider with just one or two of the three points, but in order to be truly successful in the sport, you had to possess all three. As an adult, I’d argue that there are far more complexities than we originally imagined, but the core concept of the triangle stays the same. Without certain advantages, certain levels of riding just aren’t accessible – no matter how hard you work.

As I’ve grown up and gained experience working and riding at show barns as well as serving as the equestrian club president at a school that offers collegiate riding, I’ve still found that riders will progress in this sport only as far as their privilege allows.

While I am extremely lucky to have financial support that has allowed me to pursue riding, I have still lost out on opportunities to those who had more money, a bigger name, a family legacy, a thinner body, or a myriad of other privileges that gave them a leg up over me. I know that I will never be an elite, top-level rider unless there is dramatic change in the industry and/or in my life. However, in turn, I have been afforded more privileges, more riding experiences, and more opportunities than many others. I have frequently encountered people who have been locked out of certain levels of competition or locked out of the sport entirely due to financial restraints, racism, lack of family support and other barriers that are not adequately addressed in the equestrian community.

Barriers at the First Level: Access to Horses

This brings me to my discussion of specific barriers to entry at different levels of the sport. For the sake of consistency between posts in this series, I’ve defined four distinct levels of involvement in English riding (see the graphic to the right).

According to my designations, riders at level one are either just getting started or don’t have competitive aspirations. They take consistent riding lessons and/or have consistent access to horses but do not compete on any sort of regular schedule, if at all. This is the most accessible level, since it does not require horse ownership, extensive investments in equipment, or extensive travel.

That said, barriers such as cost, location, and family/community support may still inhibit participation. Entry level riding lessons can vary from $25-$60 per lesson (with some barns charging even more) depending on the barn’s location, the amount of people in the lesson, and the length of the ride.

Many barns also require safety equipment such as helmets, boots, breeches and gloves that are designed specifically for equestrians. Depending on the brand, you would be hard pressed to put together a starter riding outfit for under $100, and that doesn’t even include extras like grooming supplies, tack, show clothes, training books and videos, and more. All of these add up to an estimated monthly cost of $200+, although it should be noted that all costs listed here and throughout this post are very much estimated – in actuality costs will vary widely depending on location and the rider’s unique situation.

Another challenge at this level can be finding a barn that will let you ride but not compete. Many trainers push their students to attend competitions once they have been riding regularly for a while since it looks good for the trainer to have their riders winning ribbons and also financially supports their personal competition goals. Riders without competitive aspirations or the financial means to compete often face shaming from their trainers and peers who insist that they must want to compete and if they just took an extra job or worked out a special deal then they could make it happen. Overall, while level one is the most accessible, there are still barriers to participation that adversely affect those with larger bodies, people of color, and people with limited incomes.

Barriers at the Second Level: Schooling Shows

Riders at the second level compete at local-level, unrecognized competitions – known colloquially as “schooling shows.” Schooling shows are usually smaller events with modest prizes, more relaxed rules and judging, and classes designed for horses and riders who are learning the ropes of competition. This level does not necessarily require horse ownership or leasing, but does require the purchase of at least some equipment, payment for consistent training and moderate competition fees, and some travel (varies depending on location).

Cost-wise, riders at this level can expect to pay for all the training fees and equipment in level one as well as additional competition and horse usage fees. If they do not pay for a horse of their own, they will likely have to pay an extra fee to be able to compete with one of their trainer’s horses on top of the coaching fee that they will pay for the day. They will also be asked to help pay for transportation costs, lodging costs, and all their own entry fees (around $200-$400 per show, depending on location/event). If they participate in 6-8 shows per year, they can expect an estimated monthly cost of $500+.

Additionally, riders who are not white may face discrimination for expressing their goals or desire to ride at this level, especially as they encounter people outside of their “barn family” at competitions. At some barns, they may be given fewer opportunities to advance because their trainer believes that they won’t be able to afford it, won’t want it, or ultimately won’t be competitive at shows because of the biases in judging. Many black riders specifically have reported microaggressions such as questions/comments about their hair or other competitors assuming that they are grooms/hired help rather than fellow exhibitors as well as more overt discrimination such as unfair judging, exclusion from opportunities, and the use of racial slurs.

Riders who have larger bodies, especially women, may face similar challenges of disbelief in their goals, being scored lower than riders with smaller bodies, and being given fewer opportunities under the guise of animal welfare. While it is true that horses have a recommended weight limit of approximately 20% of their body weight, in some instances equestrians will use this rule to fat-shame or discriminate. The 20% weight rule indicates that the average smaller-breed horse (weighing around 1,000lbs) should be able to carry riders weighing up to 200lbs and larger breeds (weighing around 1,500lbs) should be able to carry riders weighing up to around 300lbs, or potentially more if the rider is well-balanced.

It should also be noted here that men, although they often weigh more than women, are rarely locked out of riding opportunities because of their weight and, in many instances, overweight riders are conscious of their weight and careful not to harm the horse – taking extra precautions like checking saddle fit, engaging in riding activities that are less concussive for the horse, and choosing an appropriately-sized mount.

Barriers at the Third Level: Recognized Competition

Riders who compete at the third level compete at recognized competitions. For English riding in America, this means that they are almost definitely members of the United States Equestrian Federation (USEF), the governing body of equestrian sports in the United States, meaning that they can collect points in USEF-rated competitions and establish a show record.

Recognized competitions come with larger prizes than schooling shows, but also have stricter rules and judging, more competitive classes, and more expensive entry fees. In order to be competitive in these tougher classes, a rider at this level will almost definitely own or lease their own horse. Purchasing will likely cost upwards of $20k for a competition-quality mount unless they are willing to do most of the training themselves, and leases on a well-trained horse can range from $10k to well over $50k per year. Riders at this level will also own and maintain all of their own equipment. If they show approximately 2x per month, they can expect monthly costs to come out somewhere around $2,000+.

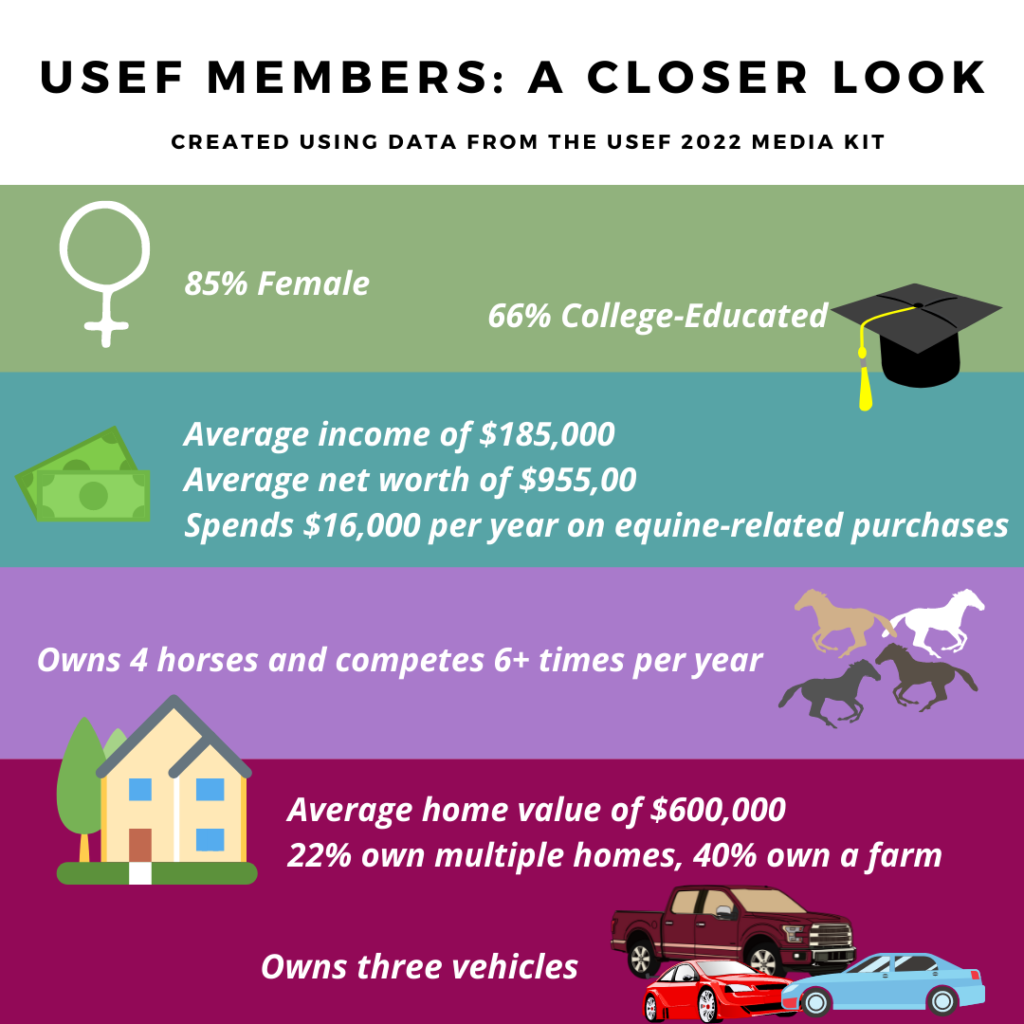

According to the United States Equestrian Federation 2022 Media Kit, the average net worth of a USEF member (which indicates eligibility to compete in recognized competition) was $955,000 with an average yearly income of $185,000. That same year, data from The U.S. Census Bureau indicated that the average American household headed by a white person earned about $70,000 per year with an average net worth of $162,770, while the average American household headed by a black person earned about $41,000 per year with an average net worth of $16,300.

These numbers alone indicate that recognized equestrian competitions are inaccessible for the majority of Americans, especially black Americans. Clearly, the average household in both listed racial groups falls far below the average wealth of a USEF member – however, the census data clearly lays out how much more “above average” a black household has to be in order to fit into this elite club of competitive horsemen and women.

Even for riders who can afford to compete, their natural size or shape may exclude them from winning ribbons. Most English disciplines in America are judged subjectively, which leaves room for judges to incorporate their own biases into how they award the top prizes.

Furthermore, the first riding competitions were available only to male riders, which allowed room for a tall, lean, long-legged figure with as few curves as possible to become the “ideal” in traditional judging.

The phrase “Big Eq Diet” is a casual reference to junior riders starving themselves in order to be competitive in equitation (a discipline judged on the rider’s position, style, and ability) and its casual use among riders at this level demonstrates a tolerance for body-shaming and the cultivation of eating disorders within the entire equestrian community.

Barriers at the Fourth Level: Elite Competition

Level four consists of riders who compete regularly at the most prestigious competitions in the nation and internationally. These riders likely own or lease a string of horses that are each valued in the six figures and pay thousands of dollars most weekends (or weeks for bigger shows!) of the year in competition and travel fees. Professional riders may seek sponsorships to cover these costs, but USEF has numerous bylaws that make it difficult for riders who do not want to be classified as professionals to accept funding, forcing them to pay out of pocket. Accounting for board, lessons, and competition-related fees nearly every weekend, riding at this level has an estimated monthly cost of $6,000+.

The riders who end up on posters, in marketing advertisements, shared on big accounts on social media, and selected to represent the United States internationally are part of this group. This level is also the most glaringly and overwhelmingly whitewashed. 89% of USEF members are white, and no person of color has ever represented the United States at the Olympics.

Additionally, while body type does not matter as much in the disciplines that compete in international competition due to more objective judging rules, the junior equitation divisions are often used as an opportunity to scout for future talent to fill the teams. Many of the United States’ international equestrian team members have a background in the “Big Eq” divisions that, as discussed above, are highly subjective and infamous for perpetuating body-shaming and unhealthy eating habits.

These riders also often have a family legacy in the sport, or at least family wealth, which effectively puts people of color at a disadvantage. As I’ll examine in further entries, and is demonstrated by the net worth figures reported by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation above, most people of color do not have the financial mobility to participate in our sport because of the long history of people of color being shut out of the same opportunities as white people in America.

Overall, racial discrimination, body-shaming, and financial costs each play a role in making English riding in the U.S. an elitist pursuit. Barriers to entry exist at every level and, if not addressed, will continue to affect the sport and people’s perception of it in a negative way.

Everyone who has chosen to make horse-back riding part of their lives has firsthand knowledge of how beneficial it can be. We all understand the therapeutic effect that horses can have on our lives, the discipline, grit, and character that the sport teaches, and the feeling of being involved in something greater than ourselves that comes from being able to start a conversation with any stranger we come across that rides too.

If we want to keep those benefits and even improve upon them, then we cannot gate-keep them. Hard work will always be a requirement of the equine industry, and we have to make sure that everyone has the same opportunity for their hard work to count. Inclusion will allow us to draw on new talent, new ideas, and new perspectives, but we can’t reach that goal without recognizing the problem and starting a conversation on how we can do better.