Comparing Barriers to Entry in English Riding Disciplines

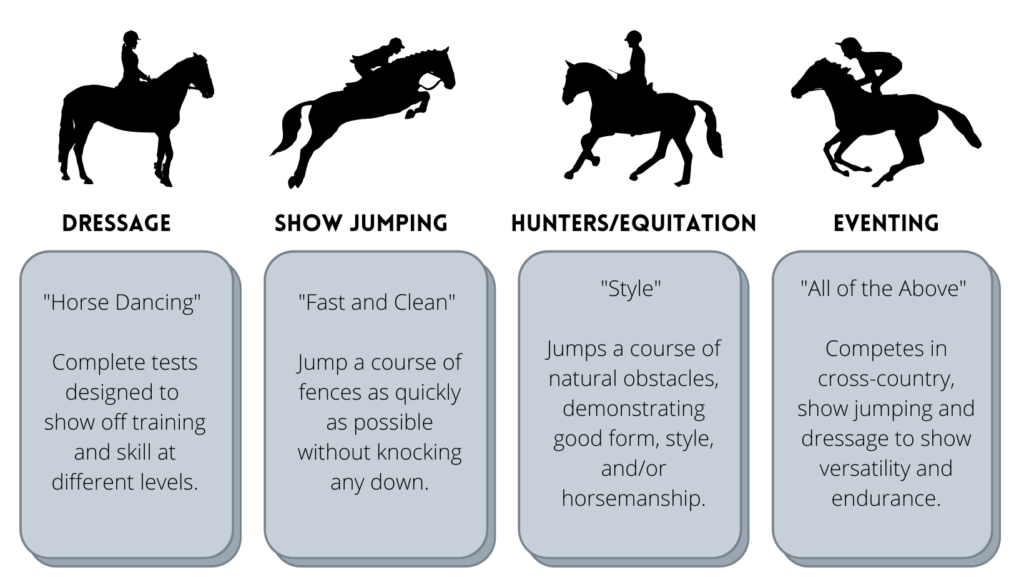

I have spent the entirety of this series investigating the issue of barriers to accessibility in competitive English riding – specifically cost, weight stigma, and systemic racism. I’ve done this thus far through the lens of four levels: access to horses/riding, local shows, rated shows, and elite-level competition. However, that system fails to account for the differences between different English disciplines. In the following final entry, I’ll examine how cost, weight stigma, and racism affect the disciplines of eventing, show jumping, hunters/equitation, and dressage.

Dressage

Dressage is derived from the French word for “training,” which reflects its military history dating back to the ancient Greeks, when cavalry officers had to develop excellent relationships and training with their horses so that they could quickly adapt to the demands of the battlefield. In Europe, aristocrats began to show off their horse’s training in pageants, and competitive dressage was added to the Olympics in 1912 although only military officers were allowed to compete until 1953. Modern dressage competition is designed for horses and riders to progress in training slowly but surely, completing tests that become more and more difficult as they move through the levels. Tests are developed on the “Training Pyramid” which encourages riders to train – in order – rhythm, suppleness, contact, impulsion, straightness, and then collection.

American dressage is governed by the United States Dressage Federation (USDF) and the United States Equestrian Federation (USEF). In terms of cost, USDF membership costs $90 per year while USEF membership costs $80 – many rated shows require proof of membership to both organizations in order to enter the competition at all. Class fees are generally $45-$50 per class, with additional fees for competing in championship classes, stabling your horse at the host facility, not stabling your horse at the host facility, “non-member” fees for those who aren’t USDF/USEF members, office fees, and fees to cover USEF procedures such as drug testing. In short, these shows can quickly become extremely expensive.

Additionally, dressage requires specific riding clothes and tack. Dressage saddles have longer flaps and deeper seats, which allows the rider to stay in the saddle better and lengthen their leg. Only certain bits and bridles are allowed, so riders may also need to purchase extras of those as well as polo wraps for their horse’s legs. In terms of clothes, riders are expected to wear white or light-colored breeches, tall boots, a show jacket and shirt with collar, and protective headgear. As outlined in my second entry, this can easily range from $350-$4,000+ per outfit.

While anyone can practice dressage (and in my opinion any English rider should), to be competitive at the higher levels of dressage requires consistent training and a quality horse with expressive movement, a pleasant temperament, and an extremely sound/healthy physique. Dressage instructors are often certified, which is not always the case in other disciplines, and so dressage lessons typically cost more than they might at the average English riding barn.

Additionally, horses that are bred specifically for dressage are often extremely expensive, with untrained prospects selling for upwards of $10,000 and young, but trained and well-bred horses easily clearing $50,000.

Partially because these horses are so expensive, dressage riders are infamous for their meticulous care. It is not uncommon for barns that service mostly dressage riders to have mechanical hot walkers (machines that exercise your horse for you to help with warm up or cool down), high-quality arena footing (easily $6,000 for a standard size dressage arena), and routine visits from veterinarians, chiropractors, saddle fitters, and acupuncturists to help keep their horses in the best possible condition.

Dressage is also infamous for being elitist, although many top riders in the discipline currently do not come from wealthy backgrounds. Still, weight stigma and racist microaggressions are prevalent. One rider wrote about her experience at her first dressage show, where a group of women watching her ride gossiped viciously about her weight and assumed that she was an ineffective rider because of her size. Juliana Schmidt, a dressage rider of Colombian descent who was interviewed for the Equestrians of Color photo project, said

“It is unfortunate, but the equestrian industry is very judgmental; judgmental of riding, clothing, horses, and skin color. Very rarely do I see equestrians of color competing in the higher levels of competition, it is mainly white individuals. Riding horses is deemed as a luxury sport, not many people can afford to keep and show horses. While I love this sport, it has many downfalls, for people of all color, but especially people of color.”

That said, I’ve discussed in previous entries how scoring in dressage can help to mitigate the effects of bias. While ringside gossip is nasty, and it remains the case that people of color are disproportionately affected by the cost barrier, in theory, any rider with a nice horse should be able to go far in dressage. This is because each rider in a dressage competition competes the same series of movements and is scored on the same metrics. Each movement receives a score out of 10, which judges must give along with their comments justifying their score, and then award collective scores for gaits, impulsion, rider position, effectiveness of the rider aids, and submission. In this way, judges are held accountable for their decisions and, while imperfect, scoring is usually accepted as fair.

Show Jumping

According to the USEF website,

“Spectator friendly and easy to understand, the object for the Jumper is to negotiate a series of obstacles, where emphasis is placed on height and width, and to do so without lowering the height or refusing to jump any of the obstacles. The time taken to complete the course is also a factor. The Jumping course tests a horse’s athleticism, agility and tractability while simultaneously testing a rider’s precision, accuracy and responsiveness. Perhaps most importantly, Jumping tests the partnership between horse and rider.”

Essentially, the objective of show jumping is to jump a course of fences quickly and without knocking them down. It is known for being much more laid back than dressage, hunters, or equitation, with fewer rules and expectations for the horse and rider presentation, more diversity in terms of breed representation, and overall having a more relaxed atmosphere around it. This may be because jumpers are judged completely objectively. There are numerous formats, but there is absolutely no way for bias to influence judging in jumpers. The horse that wins is always the horse that goes the fastest (or the closest to the target time) without knocking over any jumps.

In terms of cost, jumper classes can range from $10-$15 at local shows to $200+ for Grand Prix classes. Rated competitions also require USEF membership (or “non-member” fees) and many of the same fees outlined in the dressage section above. However, trainers are often easier to find than in dressage and horse expenses generally aren’t as high unless you are competing at the highest levels. While showjumpers obviously need to be sound and healthy, horses with conformation flaws or poor movement (both factors that would lower their price) can still reach the top of the sport if they are athletic enough to make up for it.

For me, as a junior rider that felt constantly rejected and ashamed of my body in the equitation and hunter rings, the jumper ring was my refuge. It was the one place where I knew that I would deserve the ribbons I got, and that if I rode better than the girl next to me, I would be rewarded for it. It was a place where, if I was having a good day, I even stood a chance of beating my trainer. Even though I often competed against riders who had more experience, more money, or better-trained horses, I always felt as though the playing field was equal when I went into the ring.

In college, when I didn’t make the equitation teams, I could still go in the jumper ring and win, which was key to building my confidence at a time when I didn’t feel like I was good enough.

Although I cannot speak for every rider’s experience, especially riders of color, and it remains true that cruel conversations outside of the ring won’t be affected by judging standards, I can imagine that objective judging goes a long way towards increasing morale and accessibility for others as well.

Hunters/Equitation

For the sake of concision, I’ve combined hunters and equitation into one section. Hunters are an exceptionally American discipline, but have roots based in European foxhunting and steeplechasing, where horses were required to jump natural obstacles and have a calm temperament. Modern show hunters compete to showcase their horses jumping style, bravery, and temperament, usually over a course of 6-8 fences decorated to appear like obstacles that a horse and rider may encounter if riding out in the field. Alternatively, equitation classes are designed to test the rider. Hunter seat equitation classes test the rider’s form and style over natural obstacles in hunter-style tack, while jumper seat equitation classes test them over courses that would be more likely to be found in the jumper ring and have different tack requirements.

I’ve grouped these two disciplines together because they often go hand-in-hand and both are judged subjectively. While hunters are judged on the horse and equitation is judged on the rider, both disciplines are ultimately given a score out of 100 (which, at smaller shows, is often not even announced) based on the judge’s discretion.

Interestingly, these two disciplines are also likely the most accessible in terms of breaking into the sport – hunter/equitation trainers are a dime a dozen in the United States and plenty of schooling shows offer hunter classes at a low cost since the courses are simpler to design and judge than jumpers or dressage. Costs, while not cheap, are not higher than any other discipline until you reach the top levels and start looking for very nice horses.

However, the hunters and equitation, especially the equitation, appear to be the worst offenders when it comes to weight stigma and racism. This article published in Horse Nation documents stories of body-shaming in the hunter and equitation disciplines, with disturbing accounts of upsetting beliefs, and unhealthy eating and workout habits being inflicted on children as young as seven years old.

I’ve spent a great deal of time in this series arguing for more objective judging in these disciplines, and this is just another reason why. Encouraging children to starve is unacceptable, and it is vital that we examine the systems that perpetuate that sort of behavior in trainers, parents, and judges.

Eventing

Finally, eventing is the equestrian triathlon. Horse and rider combinations compete in dressage, cross-country, and show jumping, where they try to accumulate as few faults as possible across the three phases. The discipline originated as a test for cavalry riders to test their horses in different environments, and has evolved into a popular international sport. Eventing is governed by the United States Eventing Association (USEA) and USEF.

In general many riders are attracted to eventing because of its objective judging standards and more affordable price points – especially as riders move up the levels. While jumpers, hunters, equitation, and dressage all quickly become exorbitantly expensive at the upper levels, this is less so the case with eventing. For example, this rider compared show jumping and eventing and found that she would save nearly $2,000 per show by pursuing eventing instead.

Eventing is also more “amateur-friendly.” While many rated hunter/jumper shows take place throughout the week, with classes for amateurs (people who are not paid to ride or train) scheduled on weekdays leading up the exciting professional classes on the weekends, most eventing shows have amateurs and professionals competing against each other and take place entirely on the weekend. Each competitor also has assigned ride times, so they know exactly when to be at the competition and, more importantly, when they can go home and get back to work/childcare/life.

That said, startup costs may be higher for eventing than other disciplines. Three phases means that many riders end up purchasing two or three sets of tack and equipment (although eventers are known for being much more laid back about brand prestige than, say, dressage riders or hunters). That said, although eventing horses must be strong and athletic, they do not have to be exceptionally well-bred, perfectly put-together, or even fantastic movers. There are generally far more breeds of horse represented, especially at the lower levels, in eventing than in other disciplines.

So, while eventing may be more expensive or more difficult to enter than the other disciplines mentioned here, it is likely easier to progress up the levels once you’re in.

Final Thoughts

Overall, I would argue that each discipline has its pros and cons. Dressage is strong in that it has fairly objective judging standards, but at the very least needs some solid PR to overcome its elitist reputation. Show jumping levels the playing field, but can quickly become expensive as riders progress up the levels. The hunters and equitation are easy for riders to get into, but potentially emotionally, physically, and financially damaging once they do. Eventing may be less expensive to progress in and have more objective standards, but can be difficult to break into in the first place.

In general, regardless of discipline, I believe that there needs to be a culture shift in the equestrian world towards greater acceptance and inclusion of people of all backgrounds. My observations above highlight specific areas for each discipline to improve in, but it is also my hope that riders from each discipline learn from each other and work to represent their discipline well – treating others with kindness and respect.

In my research for this series, it has been disheartening to hear accounts of top trainers encouraging eating disorders in their students and of competitors making racist comments and shaming others for their weight. However, what may be even worse is seeing the wave of people who refuse to acknowledge that our sport is anything but perfect. As riders, we should know better than anyone that perfection is an unattainable, but worthy goal, and that the second you think you’ve reached it, you’re done learning.

In the saddle, the horses keep us humble, but out of the ring, we owe it to each other to hold one another accountable and try to do better.